Three Sides of Everest

There's more to a mountain than the summit.

Mount Everest rises in the distance, in a view from the north, in Tibet.

Reprinted by arrangement from the book The Call of Everest: The History, Science, and Future of the World’s Tallest Peak by Conrad Anker. Copyright ©2013 National Geographic Society.

0n a beautiful, clear morning in May 2012, I headed through a forest high above the Imja River in Nepal’s Sagarmatha National Park. Rarely used by trekking groups or visitors, it is a trail I discovered years ago while living in this region, known as Khumbu, conducting the fieldwork for my PhD in geography. The trail contours along steep, north-facing slopes that are blanketed by a thick cloud forest of Himalayan fir, silver birch, and numerous tree and dwarf rhododendrons. The national flower, the blood-red Rhododendron arboreum, was in full bloom. Old-man’s-beard lichens draped the limbs, catching moisture from the early morning mists that were beginning to lift. On either side of the trail bloomed purple and yellow primroses and blue starshaped gentians. These pioneers of spring foretold the arrival of the many hundreds of flowers to come.

Himalayan musk deer

Himalayan tahr is a relative of wild goats

Himalayan vulture

The trail emerges from the cool forest into a high-altitude shrubland of dwarf rhododendron. The most conspicuous, the sunpati (R. anthopogon), has an aromatic scent that is among the most pleasing that I have ever encountered—in small quantities, that is. Porters often complain of “sunpati headaches” if their routes take them through too many miles of the pungent shrub.

Rhododendron arboreum, Nepal’s national flower

Looming above is one of the grandest sights in the entire world—the black, pyramid-shaped, ice-clad, and wind-blasted summit of Mount Everest. Tibetans revere it as Qomolangma (“holy mother”), and local Nepalis used that name until the Nepali government renamed it Sagarmatha (a Sanskrit word often translated as “mother of the universe”) in the early 1960s for political reasons. The mountain successfully resisted all Western attempts to climb it for thirty-two years, beginning with the first British reconnaissance in 1921 through numerous attempts until Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay’s successful climb in 1953. Fifty-nine years later, in the spring of 2012, almost 400 climbers summited. Even so, the world’s highest pinnacle casts its spell on all who dare approach it.

The 1,500-mile-long Himalaya mountain range separates the Asian mainland from the Indian subcontinent. The curious band of yellowish rock that stretches across Everest’s exposed face actually began as sediments on the bottom of what was once the Tethys Ocean. Unimaginable heat and pressure over the eons caused these sediments to metamorphose into marble, slate, and gneiss, and the slow-motion collision of the northward-moving Indian tectonic plate with the Eurasian plate thrust the rocks upward toward the skies. The Himalayas are still growing, as evidenced by the frequency of earthquakes in the region. A magnitude 6.9 earthquake in September 2011 triggered massive avalanches that resulted in tragic loss of life in Nepal and especially the Indian state of Sikkim to the east, where the epicenter was located.

The southern flanks of mountains near Everest are part of Nepal’s Sagarmatha National Park.

More recent evidence of this dynamic environment includes the large gullies that are periodically flooded by torrents—spates of snowmelt or rainfall or floodwaters from glacial lakes that have burst out and sluiced down mountainsides. Less dramatic are the globular landforms known as solifluction (moving soil) lobes, where saturated soils have flowed slowly downward on steep mountain slopes.

Most people identify Mount Everest with Khumbu, or the southern side of the mountain, a region inhabited by the charismatic Sherpa people and, more recently, by Rai laborers and lodge managers from farther south. Following Hillary and Norgay’s lead, the bulk of the annual climbs, treks, research, cleanup expeditions, TV specials, IMAX and Hollywood films, and special events—such as the May 2011 summit climb and paraglide down to Syangboche airstrip by Sano Babu Sunuwar and Lhakpa Tshering Sherpa—take place on this side.

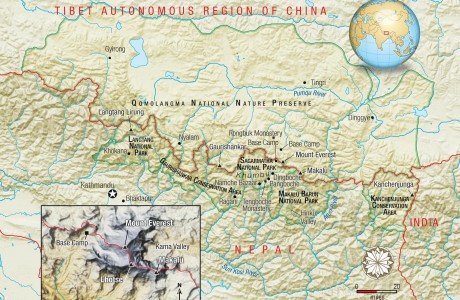

But Everest contains two other sides as well. All of the early-twentieth-century British attempts to reach the summit took place on the north side, in the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, prior to the closing of Tibet and opening of Nepal in the late 1940s and early ’50s. On the north side, commonly associated with the famous Rongbuk monastery, a road used by motor vehicles leads to Base Camp, a tent village that hosts several dozen foreign climbing expeditions per year and, more recently, thousands of Chinese tourists. Finally, the Kama Valley in eastern Tibet is the gateway to the technically challenging east face of Everest, which has been successfully climbed by only a handful of people. Since its access is so difficult, this seasonally inhabited valley is much more pristine than either of the other two sides. The Qomolangma National Nature Preserve, created in 1989, protects the valley.

Tibet’s Kama Valley, the gateway to Everest’s eastern flank, is uninhabited except for seasonal yak herders. Access to the valley is limited to several months per year because snow blocks most of the passes.

Geographically, Everest lies within the subtropical Asian monsoon zone, where more than 80 percent of the annual precipitation falls between June and September. Most of the thousands of people who visit Khumbu each year do so in the fall or spring seasons, avoiding the monsoon rain and attendant leeches found at lower elevations. Having spent a summer there in the 1980s, however, I have always felt that the Khumbu monsoon period is one of the world’s best-kept secrets. The days are normally sunny and partly cloudy until the early afternoon, when the clouds finally make their way up the valleys and to the villages. The rains, usually mild, arrive in the late afternoon or evening, encouraging the subalpine and alpine wildflower bloom throughout the period.

Monsoon clouds hover over yak herders in Kama Valley.

Red panda, an animal that is active during twilight and night hours, sleeps in trees during the daytime.

Snow leopard dines after reclaiming—or appropriating—a carcass from a group of Himalayan vultures

Access to Kama Valley is limited to only several months per year because snow blocks most of the passes during the rest of the year. Only 200 foreigners—their luggage carried by yaks, since portering is unknown in Tibet— visit the region per year. This daunting trek takes two weeks to complete, and any expedition must be entirely self-sufficient in terms of emergencies and evacuation plans. Located downwind of the Everest snow plume, the valley’s passes can also be blocked by more than three feet of snow falling over the course of one day.

On the north side of mountain, the Himalayas represent a much higher topographic barrier to the monsoon, and the region is dry year-round. Partly as a result, glaciers on the north side of Everest are retreating at a faster rate than those on the south, since little moisture replenishes the snow that would ensure their continued growth.

Ten years ago, the topic of climate change in the Everest region was practically unheard of. Today it is widely discussed among visitors and Sherpas alike. Dramatic indicators of climate change can be seen in phenomena such as the recession of glaciers and the formation and expansion of glacial lakes. Traditional planting dates are often delayed because of the late arrival of spring rains, and young crops are vulnerable to the often devastating downpours once the rain does arrive. People claim that more snow and more rain are falling than at any time in living memory. The monsoon used to end by the end of August but now extends well into, if not to the end of, September.

As on all mountains, vegetation patterns on Mount Everest depend largely on altitude, slope, aspect, precipitation, geology, and human use. On the south-facing side, warm and dry shrub grasslands were created by herders hundreds to thousands of years ago, and they now cover the highly modified, but stable, slopes. On the moist and cool north-facing slopes, fir, birch, and rhododendron forests grow. Above 13,000 feet, shrub juniper and dwarf rhododendron also contribute to the geomorphic glue that holds the thin, young, and fragile alpine soils in place. Above 16,700 feet only sparsely distributed cushion plants can survive. In 1938, the mountaineer Eric Shipton found a saw-wort (Saussurea gnaphalodes) on a slope of scree (loose rock debris) at an altitude of 21,000 feet on the north flank of Mount Everest—the world record for the highest known vascular plant growth.

Rhododendron forest in Sagarmatha National Park

In 2004, the Mountain Institute and American Alpine Club joined with local people in the upper Imja Valley to form the first Khumbu Alpine Conservation Committee. This community organization began active efforts to protect and restore its alpine ecosystems by promoting the use of imported kerosene as a fuel alternative to wood from juniper and alpine cushion plants. Juniper cover has regained a strong foothold in the last decade, but much more work remains to be done to remedy the growing problems of solid waste and human waste management.

The 3,500 Sherpa people who live on the Nepal side of the mountain in Khumbu are believed to be descendants of the original Sherpa pioneers who arrived from Tibet 500 years ago. Pangboche and Dingboche villages were already well known as meditation sites by the time of the migration, however, and Sherpa legends state that shepherds grazed their herds here well before the arrival of their ancestors. Geographer Stan Stevens writes of “certain ruins in high places in the Dudh Kosi valley” believed to have been early shepherd huts. Testing of charcoal and soil samples I have collected shows that humans began cutting and burning the south-facing Himalayan forests between 3,000 and 5,000 years ago. Fir-birch-rhododendron forest (still common on most north-facing slopes) was opened up over time, most likely by Rai or Gurung ethnic groups from the south transforming the land for cattle grazing.

A glacial river flows in Sagarmatha National Park.

At first the Sherpa people did not greet the park and its staff with enthusiasm. Reforestation exclosures built in the 1980s by park wardens were criticized as taking away valuable grazing land. Because the animals’ browsing habits heavily damage vegetation, goats were banned and removed from the park, which angered goat owners. The sudden presence of the military, assigned to patrol against poaching in national parklands, created new tensions. Regulations prohibiting the harvesting of shrub juniper in the alpine zone continued to be ignored by dozens of trekking lodges. But today many of these former attitudes have changed, and local residents now view the blue pine and fir forests reestablished on the slopes with pride.

Established in 1989, the Qomolangma National Nature Preserve covers an area of 13,500 square miles, including the Kama Valley, in the Tibet Autonomous Region of China. Compared with the Nepal side, the Tibetan terrain is generally much higher in elevation but considerably less rugged. An estimated 68,000 people live in the preserve, engaged in agriculture, animal husbandry, or both. Unlike the high-altitude plateau that most people associate with Tibet, the preserve contains a diversity of landscapes that range from subtropical, densely forested river valleys below 6,500 feet to ice-clad peaks of the Higher Himalayas at 26,000 feet and above. The preserve provides habitat for the rare snow leopard, kiang (wild ass), and black-necked crane as well as Tibet’s only populations of the Assamese macaque. Langur monkeys, Himalayan palm civets, jungle cats, musk deer, and tahrs are also found in abundance.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Khumbu was frequently cited as a case study of poor land management. Scientific and popular articles at that time proclaimed that the region was suffering from extensive deforestation as the result of a growing population, the influx of Tibetan refugees in the early 1950s, increased and unregulated tourism, and the breakdown of traditional Sherpa practices of natural resource management. At the same time, a much smaller, but equally vocal, contingent of people held the exact opposite view. “There are more trees in Khumbu now than there were in 1950, and I have the photographs to prove it,” said Charles Houston, an American physician, highaltitude expert, and member of the 1953 K2 expedition.

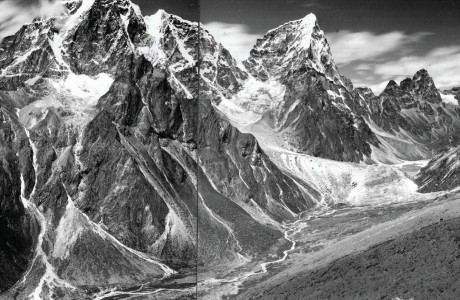

Mount Taboche was photographed by the author in 2007, top, for comparison with the composite image, above, taken in the 1950s by the Austrian climber-cartographer Erwin Schneider. The waters of a glacial lake, visible in the distance, are held back by a glacial moraine. The route toward the Everest Base Camp is upriver along the glacial river that enters the valley from the right and passes in front of the moraine.

Replicating the photographs taken by Schneider, Houston, and others in the 1950s also provided a unique opportunity to demonstrate just how dynamic a landscape the Everest region was. The scars and impacts of destructive glacial-lake-outburst floods, landslides, and torrents that had occurred in the interim could be easily seen.

In the fall of 2007, I was climbing at 18,000 feet in the upper reaches of the Imja River watershed, near where Erwin Schneider had taken one of his photographs. The view in front of me now revealed a dramatic change. The Imja Glacier that I had hoped to rephotograph was gone, replaced by a lake almost half a mile long. Icebergs as big as houses had broken off the former glacier and now floated aimlessly in the water. Dozens of such glacier lakes holding hundreds of millions of gallons of water have been created in the Khumbu region since the early 1960s. Usually contained by dams of loose boulders and soil, these lakes present a risk of glacial-lake-outburst floods. One such event in 1998 in the Hinku Valley of Makalu Barun National Park in Nepal destroyed trails and seasonal settlements for more than fifty miles downstream, and the damage is still visible in satellite images taken a decade later.

The mountain itself, however, will adapt. Mount Everest has survived the spread of humankind over the Earth, the sweep of ice ages and interglacial periods, the slow migration of flora and fauna up and down its slopes, and the recent discovery of its lower slopes by farmers, yak herders, and adventure tourists. It will continue to tower among the clouds long, long beyond human memory.

Reprinted by arrangement from the book The Call of Everest: The History, Science, and Future of the World’s Tallest Peak by Conrad Anker. Copyright ©2013 National Geographic Society.