The Sunland Grizzly

By the 1920s, California had lost all of its grizzly bears—once considered a distinct species and an emblem of the state.

Earliest known depiction of a California grizzly (in captivity), 1816

In 1916, Cornelius Birket Johnson, a Los Angeles fruit farmer, killed the last known grizzly bear in Southern California and the second-tolast confirmed grizzly bear in the entire state of California. Johnson was neither a sportsman nor a glory hound; he simply hunted down the animal that had been trampling through his orchard for three nights in a row, feasting on his grape harvest and leaving big enough tracks to make him worry for the safety of his wife and two young daughters. That Johnson’s quarry was a grizzly bear made his pastoral life in Big Tujunga Canyon suddenly very complicated. It also precipitated a quagmire involving a violent Scottish taxidermist, a noted California zoologist, Los Angeles museum administrators, and the pioneering mammalogist and Smithsonian curator Clinton Hart Merriam. As Frank S. Daggett, the founding director of the Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science and Art, wrote in the midst of the controversy: “I do not recollect ever meeting a case where scientists, crooks, and laymen were so inextricably mingled.” The extermination of a species, it turned out, could bring out the worst in people.

Cornelius B. Johnson and the Sunland grizzly in 1916

When Johnson first detected the signs of a large bear at his farm in late October, he grabbed his .30 Marlin rifle and followed the animal’s tracks for about a mile into foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains, where he lost them. The next night he laid down a heavy bear trap, anchored to a fifty-pound sycamore log, and baited it with spoiled beef. Two mornings later, Johnson awoke to find the trap—and the sycamore log—gone, and he easily followed the new tracks for about half a mile, until he found the bear, bloody and exhausted, and shot it. In his twenty years in Tujunga Canyon, Johnson had never seen a grizzly bear, so few were their numbers at this point, but he quickly recognized the telltale long claws and the grayish or “grizzled” fur and knew what he had. He brought back his horse and wagon to drag the 250-pound bear to the local butcher, had it skinned and butchered, and sold off cuts of the meat to the locals. He saved the hide, the head and neck, and a shoulder of the bear, expecting they might be worth something, but he did not know how rare his find truly was.

Unbeknownst to him at the time, Johnson contributed to the permanent extinction of the California grizzly bear (Ursus arctos californicus), a subspecies of the North American brown bear, which has five or six extant subspecies today, including the grizzly bear and the Kodiak bear. At one point the California grizzly was classified as its own species, Ursus horribilis. Zoologists estimate that the California grizzly population was approximately 10,000 at its peak, around the 1820s and 1830s. The bears were a common sight to the California Indians, the Spaniards, and the flood of Americans arriving during and after the Gold Rush of 1849. “We have here grizlys in great abundance,” a rancher in Kern County complained in 1857. “[T]hey are really a nuisance, you cannot walk out half a mile, without meeting some of them, and as they just now have their clubs [cubs], they are extremely ferocious so, I was already twice driven on a tree.” A lowland and foothill dwelling animal that once roamed the entire length of the state west of the Sierras and the southern deserts, the grizzly found itself in the direct line of American settlement and enterprise. Although many grizzlies were wantonly slaughtered for sport and, sometimes, for their meat, most bear hunters killed to preserve human life and property. California newspapers of the late nineteenth century were replete with accounts of grizzlies raiding livestock and occasionally killing ranch hands who dared to obstruct their sorties. By the end of the nineteenth century, the only refuge for the grizzly was the heavy chaparral of the Santa Ana Mountains, the western flank of the Southern Sierra Nevada, the mountains of Santa Barbara County, and the San Gabriel Mountains.

Bears found temporary refuge from European settlers in the Sierra Nevada mountains, as imagined by Frances "Fanny" Palmer in 1867.

But Grinnell was driven by more than scientific curiosity and the desire to enhance the prestige of the Berkeley museum. He was also compelled by the thrilling sensation of proximity to wildness and danger. As a boy in Pasadena, hiking with his father in the San Gabriel Mountains, Grinnell had seen abundant evidence of grizzlies, many of which ransacked local apiaries for their honey at night. But Grinnell had never seen a live grizzly. “I was obsessed only with the spirit of adventure, the yearning to ‘kill a bear,’ as two or three other Pasadena boys had done,” he later wrote. He often wrote admiringly—perhaps a bit enviously—about a particular boy who had the fortune of shooting a fullgrown male grizzly in Big Tujunga Canyon. Stories of these close encounters with grizzlies were likely fresh in his mind when he drove to Johnson’s ranch to verify that the remains were, indeed, those of a grizzly bear, albeit a small one. Johnson welcomed the scientist but delivered bad news: he had sent off the pelt and skull to a taxidermist, A.G. Booth.

Grinnell and Johnson visited Booth together, and Grinnell saw “the skull, still in the flesh showing every feature of a grizzly.” But Grinnell wrote in his field notes that Booth “was wise to its great value, and proposed not to let it out of his hands under any consideration.” Later Johnson agreed to sell the skull for thirty dollars after Booth was done with his work. After all, Booth did not need the real skull to preserve, stuff, and mount the head. Grinnell paid Johnson for the skull in advance and wrote in his field notes that Johnson was a good and “absolutely trustworthy” man.

But Booth was a different story, and Grinnell had good reason to worry about him. In 1906, Booth had been arrested for warehousing the spoils of three Yellowstone poachers who’d threatened to kill anyone that interfered with their operation, and who probably were responsible for the murder of a Yellowstone game warden. The Los Angeles game warden had found, via a secret door beneath Booth’s shop, more than 150 elk horns, heads, hides, scalps, and teeth worth more than $10,000, “the largest confiscation of taxidermy supplies ever made in the United States,” according to the Los Angeles Times. There was not enough evidence to convict Booth of a crime, but the three poachers were convicted under the Lacey Act, the landmark conservation law passed in 1900 and vigorously enforced under the presidential administration of that celebrated outdoorsman, Theodore Roosevelt.

When Johnson and Grinnell returned to Booth’s shop to follow up, they found Booth with a cleaned skull, which he promised to hand over when the job was done. But Grinnell recognized that the specimen was the skull of a polar bear. Grinnell kept quiet—he worried that confronting Booth would only diminish his chances of ever getting the real grizzly skull. Later Booth told Grinnell that if he wanted the skull (the polar bear skull that he was falsely presenting as a grizzly skull), he would have to bid against Grinnell’s good friend Frank S. Daggett at the Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science and Art.

Grinnell soon called Daggett to confirm that Booth had contacted him. And then, in a rare moment of pettiness, Grinnell betrayed his friend by not disclosing that the skull presented as a grizzly was in fact a polar bear. “I felt resentful towards you,” Grinnell later confessed to Daggett, “for at least countenancing any scheme which Booth might be contriving to keep me from getting the real skull.” Daggett, of course, had no knowledge that Grinnell was trying to get the skull for himself, and was a complete innocent in the affair. And as a result, Daggett bought the polar bear skull for the Museum. For the next two months, Daggett believed that he had a genuine California grizzly skull in his museum until Clinton Hart Merriam revealed its identity.

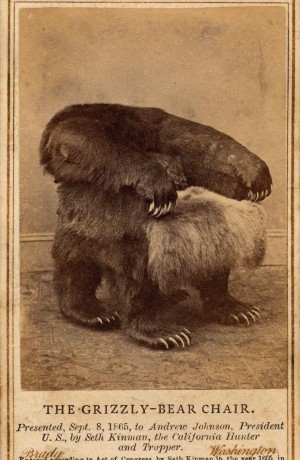

Novelty made from a California grizzly carcass

It is now high time for me to combine with you, to save that Sunland grizzly skull. For I am morally certain it is a Grizzly, as I saw not only the hide and claws, but also the uncleaned skull the teeth of which I examined. My advice now is not to scare Booth in any way (so that he might scent criminal proceedings), as he might in a pinch destroy outright the real skull. He, and no one else apparently, knows where the real skulls is, and it is that that you must put your wits to getting him to cough up—for the sake of science. I don’t care a snap about seeing Booth convicted—but rather to see the skull available in some Scientific Museum, preferably in this state, where it belongs. Of course, I wanted it to come here.

Daggett, still smarting from his wounds, was disinclined to follow Grinnell’s advice. Instead, he had officials accompany him to Booth’s shop, where he returned the polar bear skull and recouped the County’s money.

But Booth was relentless in his determination to make a profit from the whole affair. Shortly after the Christmas holiday, he drove out to Johnson’s ranch and produced a third skull, much bigger than the polar bear skull and more likely, he figured, to deceive Daggett and his staff and fetch a nice price. When Johnson brought the skull to Daggett, as Booth had suggested, Daggett fired off a telegram to Grinnell asking him to express the “condyles”—the tips of the shoulder bones that Grinnell had dug up at Johnson’s property—so that his staff could compare them against the third skull. It did not take long for them to determine that it was not a match.

As the year wore on, Grinnell and Daggett grew apart, communicated less frequently, and reconciled themselves to never finding the real skull. Daggett sent Grinnell a letter early in 1918 in which he shared the tragicomic news that Johnson, convinced that no American scientist could be trusted, had shipped the third skull to the British Museum for authentication. However, he wrote: “I have no more personal interest in the matter.” “Under the circumstances,” Grinnell wrote back, “I do not care to figure further in the affair.” If Grinnell and Daggett had any more communication, there is no record of it. Daggett died suddenly of a heart attack in April of 1920, and Grinnell never knew how much his deception had wounded the man. In a letter to Merriam at the height of the confusion, Daggett accused Grinnell of having “deliberately planned to discredit me with you, and incidentally with our scientists on the Coast.”

Meanwhile, Booth kept scheming. In August of 1921, he tried to exploit Daggett’s death by attempting to sell, through an intermediary named John Rowley, the skull of the “Sunland grizzly” to the new director of the Los Angeles County Museum, William A. Bryan. But Bryan quickly learned the story. “I am confident,” the ornithologist Luther E. Wyman wrote to Bryan, “that Booth, having once flouted science in general and this museum in particular, would not hesitate to play the same crooked game again if given the chance.” Bryan turned down Rowley’s offer, as any reasonable person would, but it was a terrible mistake. For the first time since he absconded with the skull in 1916, Booth was offering the real Sunland grizzly skull. Rowley then approached Grinnell, who agreed to examine the skull if he mailed the skull immediately to his laboratory in Berkeley. And in September of 1921, Grinnell lined up the condyles with the skull—they were a perfect match, complete with the unique butcher’s knife marks inflicted in 1916. Joseph Grinnell had recovered the Sunland grizzly, the second-to-last California grizzly known to this day. The last was killed in Fresno in August of 1922.

The Sunland grizzly skull proved to be much more than a vanity piece for Grinnell. He used its molars to establish a definitive test for distinguishing the remains of grizzly bears from those of all other types of bears. His published description of that analysis is in his monumental two-volume work Fur-Bearing Mammals of California (1937). He greatly enriched the natural history holdings of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at Berkeley. And, in the process, he got to reexperience his childhood excitement and fascination with the elusive California grizzly. But he must also have wondered if it was worth it. (Incidentally Grinnell received a letter in 1939 claiming that the grizzly Johnson shot had been no local native, but an escapee from the Griffith Park Zoo, which opened in Los Angeles in 1912; he likely dismissed it as being from an eccentric, and did not reclassify his specimen.)

California adopted the "bear flag" as the state flag in 1911, four years before the Sunland grizzly was shot.