Conservation Alert

![]()

July-August 2007

| ||

The vaquita, the world's smallest porpoise, lives only in the northern Gulf of California. It often drowns in fishing nets as bycatch, and just 200 individuals remain. Can the species survive?

By Robert L. Pitman and Lorenzo Rojas-Bracho

“Vaquita!”

Two on-duty and three dozing off-duty observers spring to attention on the flying bridge of our research vessel under the suffocating heat of the Mexican sun. The shouting observer checks the readings on her binoculars, but she can barely check her excitement: “Twenty-two degrees left of the bow, about 1,200 meters away. Looks like a mother and calf swimming together!”

Momentary mayhem breaks out on the flying bridge as members of the survey team tussle for binoculars and jockey for position. Everyone wants to see the world’s most endangered marine mammal.

We have been looking for vaquitas for more than a week with little success, here in the northern reaches of the Gulf of California, Mexico. The gulf, also called the Sea of Cortez, is the thousand-mile-long spear of ocean wedged between the mainland of northwestern Mexico and Baja California. There is no wind: the ocean’s surface looks like stretched Saran Wrap. The air temperature climbed above 100 degrees Fahrenheit just after sunrise this morning and hasn’t looked back.

|

But the austerity surrounding the gulf belies the productivity just beneath its surface. Seasonal winds and a thirty-foot tidal range dredge up cool, nutrient-rich waters that support an enormously productive marine food chain. The gulf is home to large populations of blue whales, fin whales, and sperm whales; throngs of common dolphins charge about in schools that number in the thousands; multitudes of breeding seabirds crowd together on cactus-studded islets. The stark contrast between the relatively barren terrestrial landscape and the lush marine seascape is a defining paradox evident everywhere in the gulf.

Tucked away in the northernmost extremity of that abundant ecosystem lives the entire world population of the vaquita—a cetacean, as are whales, dolphins, and the five other living species of porpoise. (Porpoises are distinguished from dolphins in having teeth that are flat, like chisels, instead of round, like pegs.) The vaquita was first recognized as a new species in 1958, on the basis of three skulls found on beaches in the northern gulf. But a quarter century passed before a live animal was scientifically documented, and only in 1985 were its external features first described by biologists.

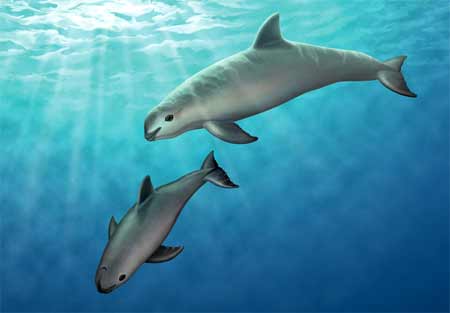

In addition to being the rarest of cetaceans, the vaquita is also the smallest. Its torpedo-shaped body measures less than five feet from snout to tail; calves are just twenty-eight inches long at birth, the size of a large loaf of bread. From a distance, the vaquita appears drab gray with a lighter belly, but at close range some intriguing details in the paint job emerge. A black stripe runs forward from each flipper to the middle of the lower lip, so the animal appears to be holding its own bridle. It has a black, circular patch around each eye. And its black lips set off a haunting little smile: Mona Lisa with black lipstick.

| ||

But the vaquita has no reason to smile. The world population of vaquitas is probably about 200 individuals—you can see more people in a Wal-Mart on a busy weekend. And though Wal-Martians are definitely in no danger of extinction, the vaquita is losing market share. Gill nets—nearly invisible fishing nets set in the water like curtains and often left unattended—are the single greatest cause of vaquita mortality each year. Vaquitas become entangled and drown when they swim into the nets by accident; or they might be lured there by fish that are already stuck. Vaquitas aren’t the intended targets of any fishery; they’re merely the bycatch of local fishermen trying to earn a living—collateral damage.

With the vaquita’s population in steady decline, its distribution in the northern gulf has also contracted, so that its range is now the smallest of any marine mammal. Nearly the entire population lives in a region less than forty miles across. To put that into perspective, while on surveys throughout the gulf, we have seen a few dozen vaquitas over the years. But never have we seen one without being able to look up and see Consag Rock, a 300-foot-tall, guano-covered spire in the middle of the northern gulf.

Even the vaquita’s scientific name, Phocoena sinus, acknowledges its claustrophobic range. Phocoena is derived from both the Greek and Latin words for “porpoise”; sinus is Latin for “bay” or “pocket,” and refers to the animal’s restricted home waters. (The common name, vaquita, means “little cow” in Spanish—a rather fitting name now that biologists know that all cetaceans are the product of a successful re-invasion of the ocean by terrestrial ungulates.)

At a recent forum convened in San Diego to address the fate of the vanishing vaquita, the organizers displayed a gallery of nearly every known photograph of the species. Most showed a dead animal swaddled in gill net in the bottom of a fishing boat, that innocent smile frozen on its face in death as in life.

|

The best estimate of the world’s vaquita population to date comes from a 1997 shipboard survey of the vaquita’s known range, which was conducted by the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service in collaboration with Mexican investigators. From the survey data, Armando Jaramillo-Legorreta, a Ph.D. candidate in oceanography at the Autonomous University of Baja California in Ensenada, and several of his colleagues estimated the vaquita population at 567 individuals.

To determine whether the population is growing, declining, or holding steady, one must know, among other things, its mortality from both natural and human causes. The latter is essentially the number of animals that die in nets every year, and that critical piece of information was supplied by Caterina D’Agrosa, now a postdoctoral fellow at Arizona State University in Tempe. Between January 1993 and January 1995, as part of her master’s thesis, D’Agrosa had interviewed fishermen and placed observers aboard fishing boats, primarily in El Golfo de Santa Clara, one of the three main fishing communities in the northern gulf. Extrapolating from her sample, she estimated that seventy-eight vaquitas were being killed annually, an overall population decline of about 10 percent per year. At that rate, a population of 567 individuals in 1997 would have plummeted to about 200 by now.

Beyond those population estimates, and despite numerous surveys to observe vaquitas in the wild, little is known about their biology or life history. Because the animal is shy as well as rare, it has not readily disclosed its secrets. But what little is known does not bode well for its future. The normal lifespan is probably twenty years or more. It reaches sexual maturity between three and six years of age, and females apparently give birth to a single calf every other year. It typically travels alone or in mother-and-calf pairs. A recent study determined that the species has little or no genetic diversity; it may have passed through a population bottleneck at some time in its past, or evolved from a small founder population. The combination of low numbers, late maturity, low birth rate, and low genetic diversity makes the vaquita vulnerable to extinction, even without such strong pressure from people.

In 1993, as a result of public and scientific outcry about its fate, the Mexican government created the Upper Gulf of California and Colorado River Delta Biosphere Reserve [see map below]. Within the reserve, gill nets are prohibited. At the time,

| ||

In spite of the good intentions reflected by the creation of those protected areas, harmful fishing practices have continued virtually unchecked. A 2006 review concluded that there has been little or no change either inside or outside the biosphere reserve since its creation. When we visited the vaquita refuge in March 2006, we found unattended gill nets set right in the middle of it. One of us (Rojas-Bracho) recently launched a series of aerial surveys, which will provide a far better appraisal of fishing activity throughout the region than has so far been possible. But because the boundaries of the reserve and the refuge are not marked, and because there is little enforcement of the no-gill-netting rule, poor results seem all but inevitable.

Fishermen, armed with nets, are the main reason for the vaquita’s decline—just as they are for the mortality of marine mammals everywhere else in the world. Of the six porpoise species, for instance, the two that live in open oceans—and thus have the least exposure to gill nets—are faring much better than their shallow-water relatives. Populations of Dall’s porpoise (Phocoenoides dalli) in the North Pacific and the spectacled porpoise (Phocoena dioptrica) in the Southern Ocean are in relatively good shape.

For the rest, the story is quite the contrary. On the Yangtze River in China, an endemic population of finless porpoise (Neophocoena phocoenoides), the world’s only freshwater porpoise population, is in steep decline. The causes? Unmanaged fishing and rampant development on the river. The marine populations of finless porpoise are somewhat better off, depending on how much fishing is done in their home waters. The message is clear: if there’s a net in the water, a porpoise will find it.

|

||

And then there’s the baiji (Lipotes vexillifer), a dolphin that lived only in the Yangtze River. In the fall of 2006 one of us (Pitman) took part in a search for the last baiji. For the past twenty to thirty years the baiji had been recognized as the world’s most critically endangered cetacean, because of its high rate of accidental drownings in fishing gear. In a six-week survey, the searchers failed to find a single individual—and in the end, were forced to conclude that the baiji, after more than 20 million years swimming in the Yangtze, was probably extinct.

There are troubling similarities between the baiji and the vaquita, the next cetacean in line for extinction. Historically, both species occupied small, insular ranges surrounded by fishing communities. They both faced the same threat to survival: nets. Both species, like all cetaceans, were slow to mature and had long intervals between births, so even if the threats to their survival had been removed, their reduced populations would have recovered very slowly. Both had been at risk of extinction for some time. “Protective measures” were put in place for both: reserves were created and laws were crafted that made harmful fishing practices illegal in protected areas. But the reserves existed largely in name only, and enforcement was unsuccessful.

All that remains of the baiji are lessons. Extinction is real. Unmanaged fishing practices have the potential not just to reduce populations of aquatic mammals, but to catch and kill every last member of a species. And extinction can happen quickly, right before our eyes. A scientific paper published a few months before the Yangtze River survey concluded that the baiji would be extinct in twenty years if protective measures were not stepped up. But the last baiji had probably already died before that article was written.

Vaquita conservation, of course, raises thorny ethical and sociological issues. The people who live along the desert shores eke out a tenuous living by fishing in the same waters as the vaquita. They simply want to keep their families fed and improve their lot. The tragedy is that their poverty and their struggles will continue long after the last vaquita loses its own final struggle in a ball of monofilament net.

It is all too easy to imagine the end of the vaquita: An exasperated fisherman wrestles with an entangled carcass under the blazing Mexican sun. He finally extricates it from the net and dumps it unceremoniously over the side of his panga—his small, open fishing boat. As the last vaquita sinks out of sight, the last human being ever to see one goes back to pulling his net.

| ||

We need to take care of this fisherman if we want to take care of the vaquita.

As in the baiji’s case, the future of the vaquita is no longer a scientific issue. The time for surveys is over. The trend is clear, the threats are known, and the answer is simple: the nets must come out of the water. A recent socioeconomic survey of the northern gulf suggested that for about $25 million, all vaquita bycatch could be eliminated. The money would be directed toward the 3,000 or so fishermen who make their living putting nets into those waters, either to buy out their fishing gear and help them get into another line of work, or to teach them sustainable fishing practices that don’t threaten the vaquita. Economists from the U.S. and Mexico are now working to design such a program, but the money remains a stumbling block.

Maybe what the vaquita needs is a corporate sponsor. For the price of a couple of minutes of ad time during the Super Bowl, an underwriter could buy a future for the species. Corporate donations do not come free, of course—vaquitas might have to carry painted logos on their sides, like NASCAR race cars. Perhaps the species could be renamed, something like “The Home Depot ’You can do it, we can help’ porpoise.” Increasingly, people seem to be losing the ability to recognize the intrinsic value of Earth’s wildlife; species will have to earn their way to justify their survival, a sad but honest appraisal of a world losing contact with its natural heritage and hewing only to market forces.

Just so, if this little porpoise goes extinct, many people will shrug off its passing as the disappearance of an obscure species from an out-of-the-way corner of the globe: “So what?” For others, however, the loss of any biological diversity on our planet is of grievous concern, particularly when what is lost is a relatively large, warm-blooded creature like the vaquita.

The vaquita has no value as a commodity: It is too shy and small ever to support an ecotourism venture. It is not a vital link in the marine food chain. There is no cure for any human disease lurking in its liver proteins. It is just a lowly beast trying to make its way, like the rest of us. Its loss would barely be noticed.

Yet it was part of the magnificent diversity of life on Earth that our generation inherited, and it is rapidly becoming part of the dwindling legacy we are leaving behind. We have a year or two now to decide whether we are going to let this species live, or whether, like the baiji, we vote it off the island and wipe that little black smile off the face of the Earth forever.

|

- Web links related to this article:

![]()

Copyright © Natural History Magazine, Inc., 2007