Natural History, February 1936

Bird Voices in the Southland

Making “talkies” with an all star cast of native American birds

By Albert R. Brand

![]()

Associate in Ornithology, American Museum of Natural History

![]()

Photographs by Arthur A. Allen, P. Paul Kellogg, and James S. Tanner

![]()

|

| Magellan braved all seas that roll, Commander Peary found the Pole, Leander swam the Hellespont, But I have tramped across Vermont. |

HUS did Arthur Guiterman sing of the explorer who stays at home. Strange as it may seem, it is not always necessary to travel great distances to foreign lands to bring back interesting and valuable results. Right here in the United States there are treasures to be sought; treasures that in a few years may be past obtaining. The frontier is gone, but even today there are areas of no inconsiderable magnitude practically unexplored; and one need not even go so far as our newer west, for, though they are becoming scarce, little-explored regions still exist on the Atlantic seaboard and in the Mississippi Valley.

HUS did Arthur Guiterman sing of the explorer who stays at home. Strange as it may seem, it is not always necessary to travel great distances to foreign lands to bring back interesting and valuable results. Right here in the United States there are treasures to be sought; treasures that in a few years may be past obtaining. The frontier is gone, but even today there are areas of no inconsiderable magnitude practically unexplored; and one need not even go so far as our newer west, for, though they are becoming scarce, little-explored regions still exist on the Atlantic seaboard and in the Mississippi Valley.

In February, 1935, a joint expedition of the American Museum of Natural History and Cornell University set out on such an intramural undertaking. The object: photographing native wild birds and recording their voices. Particular attention was given to species that, because of the fast development of civilization or for other reasons, are becoming rare.

Dr. Arthur A. Allen, professor of ornithology at Cornell University, led the party, his special province being bird photography, both still and motion pictures; he also directed the ornithological observations, and arranged the itinerary; the writer, whose major interest for several years past has been recording sounds of native birds, accompanied the group on the journey into the southland; Paul Kellogg, instructor of ornithology at Cornell, was the technical expert in charge of sound recording; Dr. George M. Sutton, a distinguished bird artist and curator of birds at Cornell University, joined the party in Florida and Louisiana, and contributed a number of water color sketches of the rarer and more unusual species; and lastly, James S. Tanner, a graduate student, accompanied the expedition as camera-man assistant, sound recording helper, cook, and general handy man.

|

The sound equipment

One bleak morning in mid-February, two small Ford trucks loaded with cameras, sound recording paraphernalia, and camping equipment pulled out of Ithaca, New York, headed southward.

The trucks, besides transporting the party, served two other purposes. They sheltered the men for at least half the time afield, and proved that one can rest quite as comfortably in a truck as one can, let us say, in the more conventional Pullman berth. In addition, one Ford was especially adapted for sound recording. In it were mounted amplifiers, sound cameras, and several hundred feet of cable with which to connect the microphone in the field and the equipment in the truck; also this vehicle carried the sound mirror and its tripod.

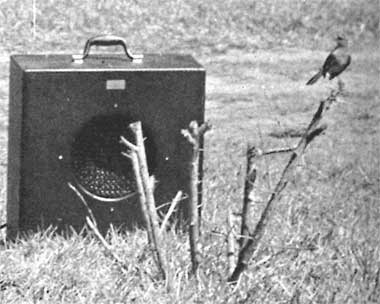

The sound mirror or reflector is a large circular disc—a section of a parabolic curve—some three feet in diameter. At the focal point of the parabola the microphone is set. The result: when the combined microphone and parabola is focused upon a singing bird, the song is greatly amplified. All other sounds not directly in the beam, however, reach the microphone in only normal volume. The object of this device is to reduce outside or ground noises, which frequently ruin otherwise excellent outdoor recordings. The mechanical ear, as the combined microphone and parabola has been called, is set on a tripod, and hooked up to the amplifier and sound camera in the truck. Most of the recordings are made using the microphone in combination with the parabolic reflector, but occasionally it is expedient to use the microphone alone.

On the prairies of Florida a six-foot diamond-back rattler was encountered. In this case the microphone was dropped close to the subject-closer no doubt than the recorder would have dared to be himself-and the snake rattled directly into the recording device; and again in a heronry in Louisiana the microphone was set among the nesting birds, and the various raucous honks, rattling croaks, and peculiar squawks were faithfully recorded.

|

The photographic equipment

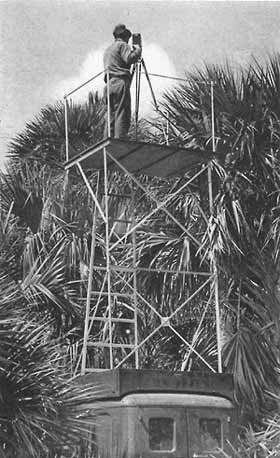

The second truck was used for photography. The Akeley camera and its substantial tripod, kindly loaned for the duration of the expedition by Mr. Duncan H. Read, was most useful and brought beautiful results; but it was a bulky affair, requiring much room, and was no joy to lug a half mile or more through virgin forest and swamp. In addition, there were several other moving picture and “still” cameras. The roof of this truck was fitted with a collapsible platform or tower, similar to those used on public service corporation repair trucks; and often the photographer stood his camera on the top of the truck, and did his “shooting” from there. Occasionally, when we were photographing birds that nested well up in the trees, the roof was not sufficiently high; then the platform was extended to its full height. This enabled the camera-man to operate from a point about twenty feet above the ground.

Outfitted in this manner the group was ready for a powderless hunt, where camera and film supplanted rifle and shot. The trophies were not to be bird skins, for the expedition was interested in preserving, not decimating, the rare species that are already all too near extinction.

It might be well to consider for a minute what we mean by rare birds. The term “vanishing birds” hardly needs explanation; generally it refers to those species that once were plentiful, but for certain reasons, persecution or hunting or what not, are now on the point of extinction. Every so often we hear of such cases. The wild turkey has all but vanished from a large part of its former range, and the final disappearance of the last lone heath hen in Martha’s Vineyard, little more than a year ago, reminds us that, do what we will, if a form becomes exceedingly scarce, all our powers are futile. Protection is of no avail. Fortunately those interesting and beautiful birds, the white herons or egrets, which were becoming extremely rare a generation ago, are again abundant.

|

One of the most outstanding examples of what one individual can do for the preservation of birds is Mr. E. A. McIlhenny’s "Bird City." He has made an artificial pond on his estate so attractive for snowy egrets that, from a small beginning, the birds have now increased to more than 10,000. Through Mr. McIllhenny’s courtesy and hospitality the expedition was able to record the curious calls of these birds, and to secure many excellent photographs.

It is to the credit of such individuals as Mr. McIlhenny and of the National Association of Audubon Societies and other conservation groups that these interesting birds are alive today. Through their efforts the birds have been saved for posterity. Not so with the passenger pigeons, however. Hardly a hundred years ago flocks were encountered so large that they literally darkened the skies. The last known specimen of this beautiful bird succumbed in captivity in 1914. Over-hunting—the bird was large, unwary, and toothsome—brought about its destruction; and almost before most people were aware that the species was getting rare it had vanished from the face of the earth.

Rare camera subjects

But what about rare though not necessarily vanishing species? Not all rarely seen birds are on the verge of extinction. There are, we are glad to say, comparatively few forms that are actually close to the border line; but, on the other hand, there are many birds that are commonly called rare. Rareness of a bird often depends upon the locality of the observer. Birds that are very rare in one place, if followed to their breeding grounds may well be as common as English sparrows at home. Others, if not common, are at least of usual occurrence.

Consider for instance Audubon’s caracara, a vulture-like hawk, which though common in Mexico and to the south, is found only in a few favorable localities in our southern states. On the Kissimmee Prairie of Central Florida the bird is a common resident, however, and it was tot difficult to find nesting birds. This region, perhaps eighty miles long by forty wide, is practically uninhabited. The only signs of civilization are occasional herds of scrawny cattle that eke out a meager existence on the sparse prairie grasses.

|

Some of the larger birds

Another bird, not uncommon on the prairie, is the Florida or sandhill crane. These large birds are true cranes, not herons; the wing spread is six or seven feet, and when standing erect their height is equal to that of a ten-year-old child. Nervous and wary as they are, photographing them was a matter requiring consummate patience and skill. The voice can be described as a loud trumpeting, rather musical and startling. Toward evening and at dawn these mighty birds fly over, trumpeting as they go. There is something awesome about their loud voices ringing over the otherwise hushed prairie; the peculiar light, the unending, flat, rolling seas of grass and palmetto, give one a feeling of reverence in the presence of powers far greater than those of insignificant man. But the sound recorder has little time for such thoughts; he must be alive to his opportunities. It was at such a time, with the prairie bathed in eerie sunlight and the cranes trumpeting overhead, that the loud stentorian calls were recorded.

Persecution has made the bald eagle a rare species in all but a few of its former haunts. At one time this bird, our national emblem, was common over most of its range. Its great size made it an easy target and, although rarely destructive, it receives protection in less than two thirds of our states. Fortunately on the coast of Florida, eagles are still fairly common, and it was on the east coast that the expedition secured photographs of these spectacular birds.

Wild turkeys also are large birds, and in addition, furnish excellent food. They have all but disappeared except in the wildest and most inaccessible regions; their future is indeed precarious. However, in Georgia, thanks to the cooperation of Mr. Herbert L. Stoddard and Col. L. H. Thompson, a flock was baited up before a blind, and sound and pictures of both male and female birds were secured.

|

Free from the fear of man

However, there is another side to the picture, and, in certain parts of Florida, birds that are generally credited with being wary and shy, have, to a large degree, lost their fear of man. In central Florida, in the heart of the city of Orlando, is a small lake. Here scaup and ringbilled ducks, coots, cormorants, and gulls congregate during the winter season. The ducks arrive in the autumn, after having migrated from their northern nesting ground. On their journey southward they are subjected to a constant barrage of lead; and on arriving at winter quarters, one would expect them to be caution itself; yet that is not so; they seem to sense that they are protected on this city lake. Here the park attendant feeds them daily, and they have become so tame that they will take food out of his hand. The residents also feed the birds, and it is really amazing to see these usually wary creatures with apparently no fear of their arch enemy, man. Hold a piece of bread in your hand above your head, and gulls will fight for the privilege of grasping it from between your fingers; while coots and ducks will churn the water at your feet in their attempts to get you to hand them a titbit.

At St. Petersburg, on the gulf coast, conditions were similar, and several species of gulls and ducks partook of the festivities. In addition, the brown pelicans have become so tame that on the municipal pier it is not uncommon to see a number of these comical, ungainly birds standing next to the fishermen patiently awaiting a handout. If a fish is caught too small for the fishermen’s creel, it is deposited in the waiting pouch of an attendant bird. It was not difficult to get the pelicans to pose for their pictures. A can of live bait, bought on the pier and fed to the birds by the hand to mouth method, lasted but a short time. The sound apparatus could not be used, however; pelicans are one of the few voiceless birds, almost as silent as that silent mammal, the giraffe.

|

Recording the ivory-bills

The most protracted stay was made in the country of the ivory-billed woodpecker. This, the largest native woodpecker, is a truly glorious bird. Slightly larger than a crow and almost as black, the ivory-billed is much more unusual and startling in appearance, especially if seen on a tree trunk as it works in typical woodpecker fashion. Both sexes have prominent crests; that of the male is a flaring red; the female’s is black. When the bird is at rest, great white patches on the wings suggesting white coat tails sharply contrasted against the greenish black of the rest of the body are strikingly prominent. The large bill is ivory-colored, as the name suggests. The species has always been uncommon; of late years it has become so rare that it is on the verge of extinction.

Ivory-bills were sought in several Florida regions, and much time and energy was expended running down every clue and rumor. Professor Allen had observed the bird ten years previously in one of the wilder regions of central Florida; and a local observer reported having seen an individual in the identical region no longer ago than the preceding Christmas. However, sight records of this bird must be taken with caution, for the other large native woodpecker, the pileated, inhabits similar regions. Confusion is all too common, and a trained observer and close observation are necessary for positive identification. Many of the casual reports of ivory-billed no doubt refer to pileated. Nevertheless there seems to be good reason to believe that a few ivory-bills still inhabit the Florida region; but actual specimens were not seen.

|

In a dense southern swamp, however, the birds are making their last stand. The large waste area is in private hands, but the birds, fortunately, are receiving the protection they so sorely need; and even visiting the region is discouraged. In fact, the expedition spent a full day of valuable time on the long distance ’phone and telegraphing, before permission was granted to enter.

The warden, J. J. Kuhn, acted as guide; he is guarding the birds’ last stand and, without his aid, finding the birds would have been well nigh impossible. But the difficulties were not over, even with the granting of permission to enter, and with the enlisting of Warden Kuhn’s aid. Miles of virgin swamp and partly submerged lands had to be navigated. As means for transporting the sound equipment and cameras, the trucks were useless; and an old farm wagon and four mules were pressed into service.

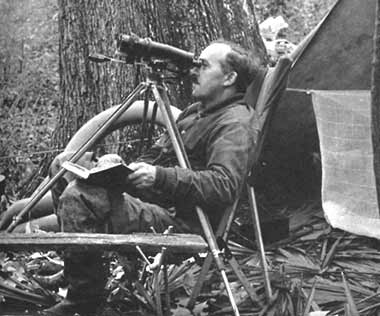

After much searching, a pair of ivory-bills was eventually located. Here, twelve miles in, camp was pitched, and for a week or more, notes were taken, photographs made, and sound recorded of America’s rarest bird. Almost exactly a hundred years ago Audubon studied this bird in the same region. It was rare in his time; little careful work had been done since, and many facts of the life cycle of the bird remain unknown.

|

Will the ivory-bill survive, or like the Carolina paroquet, the only native parrot, and the passenger pigeon, is it also doomed? Time alone will tell; but “while there is life there’s hope,” for several species that had almost disappeared, with changed conditions have later revived. It seems apparent that ivory-bills are having difficulty in bringing their nesting activities to a satisfactory conclusion; and, of course, there is no hope for a species that cannot raise progeny. As yet we do not know the exact cause of nest destruction, but the days of continued study and recording were fruitful, and furnished several clues as to what is causing the decrease. If the causes can be established definitely, it may be possible so to control them that this most interesting form, now almost extinct, can be saved for posterity.

Instead of the skins of birds, more than fifty thousand feet of film—twenty thousand feet of sound, and thirty thousand feet of motion pictures—were taken from the field, to be preserved for future study. It is hoped that the rarer birds may be saved for the benefit of future generations: if that is impossible, at least we shall have pictorial records of them; we shall know what their vocal attainments were—a poor compromise at best—but far superior to a record consisting of only written words.