The Antiquity of Man in America

Objects of human manufacture recently found in the Southwest

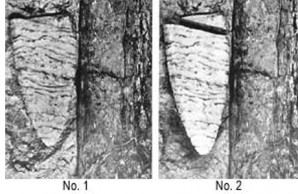

Fig. 4. Portions of artifacts associated with extinct bison. No. 1–Larger portion of artifact in contact with fragment in situ No. 2–Larger portion of artifact slightly separated from fragment in situ

As critical studies of the artifacts found associated with the bison remains near Colorado, Texas, must be left to the archaeologist, but brief detailed mention of them will be made here. There are two or three private collections of arrowheads that were picked up on the surface in the vicinity of Lone Wolf Creek, all of which have been examined by Mr. Cook and Mr. Boyes. None contained examples approaching in similarity, either in form or workmanship, those found with the bison skeleton. The latter are of grayish flint, quite thin, as shown in Fig. 1, and are devoid of evidence of notching, which is distinctly opposed to the forms found on the surface in that locality. Equally distinctive is their superiority of workmanship which, I am told, also applied to the example that was lost. While there seems to be no doubt that these artifacts represent a cultural stage quite distinct as compared with that revealed in the arrowheads found on the surface, it is not the writer’s intention to discuss such questions, and he will refer to the similarity of this find to that made by Mr. H. T. Martin at Russell Springs, Logan County, Kansas.

Readers who have been interested in the subject of man’s antiquity in America, are, no doubt, familiar with this discovery, which was made by Mr. Martin in 1895, and while the writer has not examined this artifact, Mr. Martin kindly sent a photograph for reproduction here; this for comparative purposes. (Fig. 2.) Dr. F. A. Lucas applied the specific name occidentalis to the race of bison with which this artifact was associated.

During the summer of 1925, Messrs. Fred J. Howarth and Carl Schwachheim of Raton, New Mexico, informed the writer of a quantity of bones exposed in the bank of the Cimarron River, near the town of Folsom, Union County, New Mexico, Later, those gentlemen forwarded examples for examination, which proved them to be parts of an extinct bison and a large deerlike member of the Cervidæ. Accompanied by Messrs. Howarth and Schwachheim, Mr. Cook and the writer visited the locality in April, 1926, and after a study of the deposit, made arrangements with Mr. Schwachheim for the removal of the overlying formation, consisting of some six to eight feet of very tough, hard clays. In June the writer sent Mr. Frank M. Figgins to supervise the removal of the bones, in which work he was aided by Mr. Schwachheim.

Fig. 5. Holloman Gravel Pit, Frederick, Oklahoma. [Total depth represented is 28 feet.]

Compared with the artifacts from Colorado, Texas, the Folsom examples are distinctly more pointed, but whether this difference in form and superiority in workmanship is traceable to individual preference and skill, the writer does not venture an opinion. He does, however, make comparisons with flints found on the surface, in the region about Folsom and Raton, New Mexico, and in this connection it is of interest to note that the latter are unlike such surface artifacts from the vicinity of Colorado, Texas,—being usually very small and evidencing far greater skill in their manufacture. The writer has examined a large part of the Carl Schwachheim collection of flints, from northern New Mexico, and Mr. Schwachheim verifies his conclusions that it contains nothing resembling the flints found associated with the bison remains near Folsom.

Until the studies now in progress are completed, the geological age of the Folsom bison will not be known. That it is of an extinct race there is no question. (Dr. O. P. Hay has kindly consented to study all of the bison material that was obtained in Texas and New Mexico, and expresses the belief that it contains three undescribed races.)

We have, then, in the Folsom arrowheads, the third instance of a very similar type of artifact being found immediately associated with extinct bison, in circumstances which lead geologists and palaeontologists to conclude that they belong to the Pleistocene age.

Having read an article dealing with the question of man’s antiquity in America by Mr. Harold J. Cook, which appeared in the November, 1926, number of the Scientific American, Dr. F. G. Priestly of Frederick, Tillman County, Oklahoma, wrote Mr. A. G. Ingalls, editor of that publication, briefly describing the finding of artifacts associated with fossil mammal remains in that vicinity. After some correspondence, and with Doctor Priestly’s consent, Mr. Ingalls forwarded this letter to Mr. Cook. Doctor Priestly’s account of these discoveries was of such a convincing nature that it could not be doubted that the Oklahoma material was of great importance. With the view of making studies of both the material and physical character of the deposits from which it was taken, Mr. Cook and the present writer joined Doctor Priestly at Frederick in January.

It was at once apparent that while Doctor Priestly recognized and understood the importance of the finds he described in his letter to Mr. Ingalls, it was equally obvious he had followed a very conservative course and the writer was not prepared for the discovery that in addition to the artifact mentioned, several others had been unearthed and no less than five of them preserved.

In his account of these finds, Doctor Priestly stated all had been personally made by Mr. A. H. Holloman, who owns and operates a sand and gravel pit about one mile north of the city of Frederick. To Mr. Holloman, therefore, the writer is indebted for a history of the discoveries, their stratigraphic position, and other items having a bearing on them.