Cellular Self-Destruction

A new genetic program for cell death has been identified.

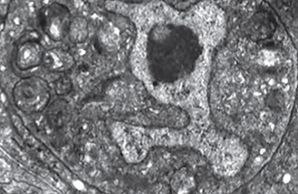

A dying C. elegans linker cell (ovoid structure) containing a nucleus folded in on itself (light gray structure), as well as abnormal organelles (dark round objects in the left portion of the cell)

The health and development of humans and other animals requires not just the generation of cells, but also their death. The process of cell death removes mutated or potentially disease-causing cells from the body, and also ensures the body’s tissues grow to the right size and shape.

The best-studied form of cell death is apoptosis, a genetic program within the cell that triggers self-destruction. Caspase proteins are integral to this process. However, in the absence of caspase proteins, and therefore the absence of apoptosis, cell death still occurs in many animals. This has left scientists searching for other, complementary genetic programs that also kill off cells.

Recently, geneticist Shai Shaham at The Rockefeller University and his colleagues found evidence of another such mechanism. They call it linker-cell-type death (LCD), identified through their work with the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans. C. elegans provides a good model in which to study cellular processes because of its relatively simple genetic make-up despite the similarity of its cells to those of other multicellular species.

In the study, the team exposed worms and their offspring to chemicals that mutated the worms’ DNA, then looked for individuals in which the cells lived longer than usual. In these individuals the scientists were able to pinpoint which genes and related molecules had been affected. One of the key proteins they identified was heat shock factor 1 (HSF-1), which normally protects cells from stress. During LCD, HSF-1 instead activates a protein complex known as the proteasome, which breaks down other proteins.

Now that the researchers have established the existence of another genetic program for cell death, they will work to understand what role LCD plays during vertebrate development. They note that a similar genetic program appears to be present in mammalian cells, and may play a role in neurodegeneration. “This work therefore could have relevance to the study of disease,” says Shaham, pointing out that uncontrolled cell death and abnormal cell survival are at the root of many human diseases. (eLIFE)